Rags & Bones is billed as a book of "New Twists on Timeless Tales", which, silly me, I thought would mean a book of fairytale retellings. (I love fairytale retellings, especially because I'm on a Once Upon A Time kick at the moment.) Although there are a couple of fairytales covered - "Sleeping Beauty" and "Rumpelstiltskin" - most are riffs on Stories that the Writers Happened to Like, which ends up being a rather broad range of inspiration, from Spenser's Faerie Queene through to Kate Chopin's The Awakening. All the stories, however, are somehow fantastical or science fictional, so it's not entirely random. I guess.

The thing with Rags & Bones is that I'm just not sure what the point of the book is. As is admittedly the case with most anthologies, the quality of the stories ranges from highly mediocre to excellent; and most of them, even the more engaging ones, don't feel like they add anything to the original text. Do we really need a retelling of "The Monkey's Paw" set in a post-zombie-apocalypse America? Why?

Without a coherent theme, the book just feels a bit like a vanity project for the editors, with Neil Gaiman's name stuck on the front to help it sell.

Reviews for the individual stories:

That the Machine May Progress Eternally - Carrie Ryan (after E.M. Forster's "The Machine Stops"). I haven't read the original, but this felt like one of the more pointless stories; an addendum to Forster's story rather than a tale in its own right. A boy wanders into a vast underground city and...that's it. It also has a rather unpleasant anti-technology slant to it.

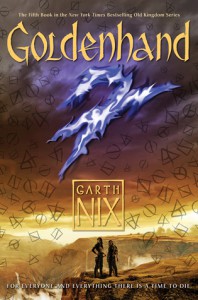

Losing Her Divinity - Garth Nix (after Rudyard Kipling's "The Man Who Would Be King"). Again, I haven't read the original. I enjoyed this one, though (in fact, I think it was probably my favourite), mainly because Nix has a real gift for worldbuilding; the story of a man who comes across a goddess on a train, there's a sense of an entire functional world sitting beyond the margins of the pages, waiting to spring into life. The ending is wonderfully creepy, too.

The Sleeper and the Spindle - Neil Gaiman (after "Sleeping Beauty"). As far as I can tell, Rags & Bones is where this story first appeared before being published as a book in its own right. A queen goes to investigate a sleeping plague that threatens her land. I was annoyed by it for the same reason I get annoyed with all of Neil Gaiman's writing: it turns female bodies into creepy decoration while doing feminist lip service. Did we really need the detail about the cobwebs between the serving girl's ample breasts? No, we did not.

The Cold Corner - Tim Pratt (after Henry James' "The Jolly Corner"). A man returns to his small home town in the American South; weird shit starts happening. I felt like it took a long time to set up its premise, and then ended where it should have begun.

Millcara - Holly Black (after J. Sheridan LeFanu's Carmilla). That title. Why. It's a retelling of Carmilla from the vampire's point of view, only set in modern-day America. Another one that felt just a bit pointless without its original.

When First We Were Gods - Rick Yancey (after Nathaniel Hawthorne's "The Birth-Mark"). In a future in which the rich can live forever by transferring between bodies, a married man falls in love with his mortal housemaid. I quite enjoyed this - as in, I wanted to keep reading for the love story - but, like "That The Machine May Progress Eternally", it felt like one of those 70s SF short stories which exist solely to point out the evils of technology. Also, "death makes life meaningful" is one of those truisms that hardly ever gets questioned. It may be true, but it's been an SF crutch for time immemorial and it's not enough nowadays to pin a story on.

Sirocco - Margaret Stohl (after Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto). On the set of a film adaptation of The Castle of Otranto, one of the star's caravans plunges over a cliff and two teenagers fall in love. Tedious.

Awakened - Melissa Marr (after Kate Chopin's The Awakening). A selkie story, and another story which kept me reading even if I didn't love it. I think it's a nicely redemptive take on Chopin's story, even if it's not as powerful; one that offers freedom as an alternative to death.

New Chicago - Kelley Armstrong (after W.W. Jacobs' "The Monkey's Paw"). The aforesaid zombie-apocalypse retelling of the story about a monkey's paw which grants three cursed wishes. There are probably interesting things you could do with this story to subvert it; Armstrong doesn't.

The Soul Collector - Kami Garcia (after "Rumpelstiltskin"). A policewoman with a troubled past has to go undercover with the criminal organisation she escaped years previously. A mysterious figure helps her infiltrate the group - for a price, dearie. It doesn't feel like a retelling in the traditional sense, but it is one of the handful of stories here that feels like it's doing something useful with the original.

Without Faith, Without Love, Without Joy - Saladin Ahmed (after Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene). One of the best stories in the book, because, again, it does something useful with the original: reimagining Book 1 of The Faerie Queene (mercifully without the rhyme) through the eyes of the Saracen knight Sansfoy, it's a story about the injustice of coopting someone into a narrative that they have no voice in.

Uncaged - Gene Wolfe (after William B. Seabrook's "The Caged White Werewolf of the Saraban"). A man rescues the wife of a dead plantation owner somewhere in Africa - but what is her secret? It's very Kipling-ish and slightly colonial and not very interesting.

1

1

4

4